How Citizen Watches and Pinball Influenced Creator Toru Iwatani

Let’s take a tour through the history of video games by examining one notable game per year. A look at the most important-slash-most interesting-slash-”this is the one we’re looking at this time and here’s why” games of the year from each year in the history of commercial video games. We’ll start in 1980 and finish around 2025 (depending on exactly how long it takes to write them up). While an effort will be applied, we’ll promise nothing definitive or conclusive — we’re on a tour, after all, which is meant to be a vacation, so don’t take it so seriously. It’ll be a series of stories, of short histories, about specific games. A look back together that will take us from the very beginning of commercial video games up through the long, windy path that gaming has so far taken.

A tech savvy family forged by the JBC

Toru Iwatani’s father was an engineer for the Japan Broadcasting Corporation. The corporation dates back to around 1925 (when “broadcasting” meant mostly radio) and was founded by the well-known and popular politician Count Gotō Shinpei.

The Count is an interesting fellow — he was not only the seventh mayor of Tokyo, but he was what we would call today a technological evangelist. He embraced technology in everything he did, and always looked for ways to use it to support the community. His community, after all.

He started technological programs, encouraged those around him to implement new technology and better themselves, and pushed the country he loved to innovate and develop as quickly as they could. And he was loved for this — he was a man so influential that when he said that the local watchmaker’s timepieces were so finely made that every citizen should be able to have one, they named the watches “Citizen” just for him.

The Count loved innovation and wanted Japan to support it as much as possible. That’s why he founded the broadcasting company that employed Tori Iwatani’s father 50 years later in the 1970s. Iwatani himself, as a young man, must have grown up around connections and electricity and wires and signals (in the times before those things were commonplace), audio and video and how to connect them and make the lines work, tune in and play things back. The Japan Broadcasting Corporation, daily, delivered simple and accessible entertainment, thanks to Toru Iwatani’s father, and the latest and greatest in applied technology. That’s the primordial soup that had been bubbling in Japan since Count Gotō Shinpei said it ought to, that Toro Iwatani’s household must have been steeped in as he grew up and as video games arrived in the mainstream in this, our first stop on what will likely be a long tour.

Pinball & Go planted the seeds for Pac-Man pellets

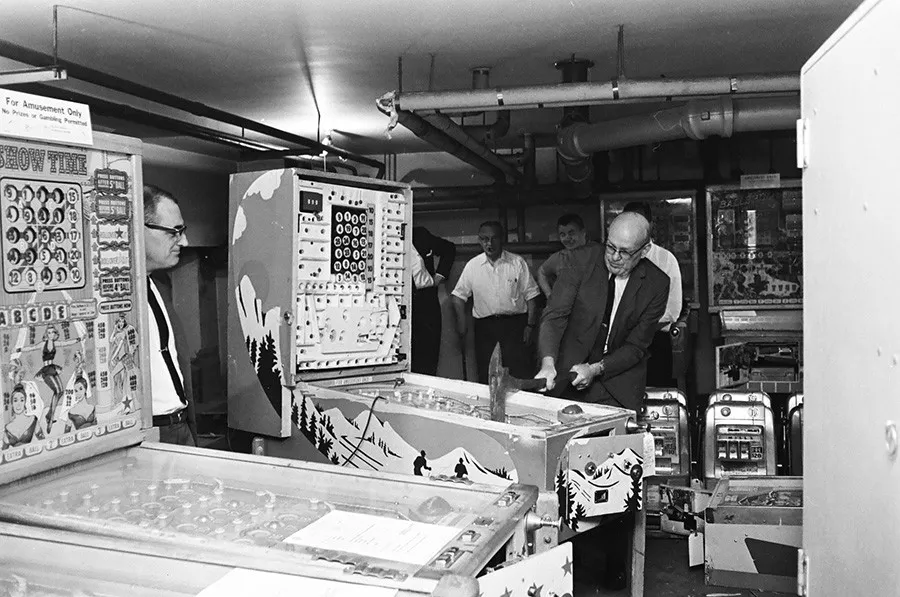

Iwatani wasn’t just his father’s son — he also loved pinball games (which were already a hit long before 1979, popularized in a coin-operated form in 1930s Chicago by David Gottlieb, whose company eventually released Qbert* and was later bought by Columbia Pictures, which itself was later bought by Coca Cola, to give you an idea of the heavily incorporated and advertising-laden future that we’re headed into with this column eventually).

Iwatani also loved board games (which have been played since the beginning of time, though in 1979, probably meant Payday, Trouble, and Mastermind — or in Japan, more likely Go and e-suguroku, both traditional board games about finding alternate routes to chase down victory across dots and grids).

Fine tuning the game & finding the Pac-Man audience.

Iwatani specifically created Pac-Man, however, because he had a frustration with his employer, and with video games in general. He was only 24 when Pac-Man was finished for the US in late 1980, but joined Namco two years earlier (which itself had rebranded in 1977 to go from amusement machines directly to video games), and had worked on a previous game called Gee Bee that combined Block Breaker with pinball. Gee Bee eventually did well enough to garner two sequels, but not well enough for Iwatani, fresh out of his home and becoming his own person. He wanted more. And he had figured something out, in 1978, about the video game industry that really bothered him.

It had a dude problem.

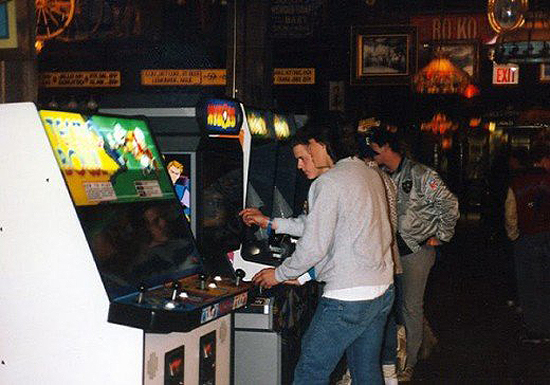

Pac-Man wasn’t the first video game hit. Space Invaders was already a huge success, and Football and racing simulators were also plenty successful. But Iwatani looked at the rest of the world and saw how small gaming actually was before this point. It wasn’t anywhere near as popular or ubiquitous as it seems today. In 1979, video games still only appealed to a very small commercial audience: young males. Nearly every title available appealed to masculine tastes, either with violence or machinery, and when it came to who played, much less spent money, on video games, that small subsegment was the extent of it.

In the late 1970s, STEM was something that came on a rose. Title IX was years away. Video games are a combination of games and technology, and it’s not just a technology problem — women were still having to sneak into marathons in 1967. Certainly many women did love video games, or at least would have if they’d been able to play them without garnering attention, positive or negative. Even today, most women aren’t very open about their gaming in public (and would rather leave their mic off, except in polite company).

But Iwatani didn’t need years of legislation and cultural change to realize that gaming’s audience wasn’t just the male half of the population: he could see it in the arcades. They were dingy, gross places, full of rowdy dudes, mostly yelling at each other and/or the pinball and arcade machines. Games were the population of bars, restaurants, arcades, and illicit gathering places, and in the 1980s, those were mostly the domain of men.

“I wanted to change that,” Iwatani told TIME in 2015, “by introducing game machines in which cute characters appeared with simpler controls that would not be intimidating to female customers and couples to try out … and couples visiting arcades would increase.” That’s the vision that fueled the industry’s first video game mascot, its first real trip into the mainstream — a friendly face on the game and a relatable quest, instead of a spaceship or sportsman.

Pac-Man and the ghosts – hunger & fear

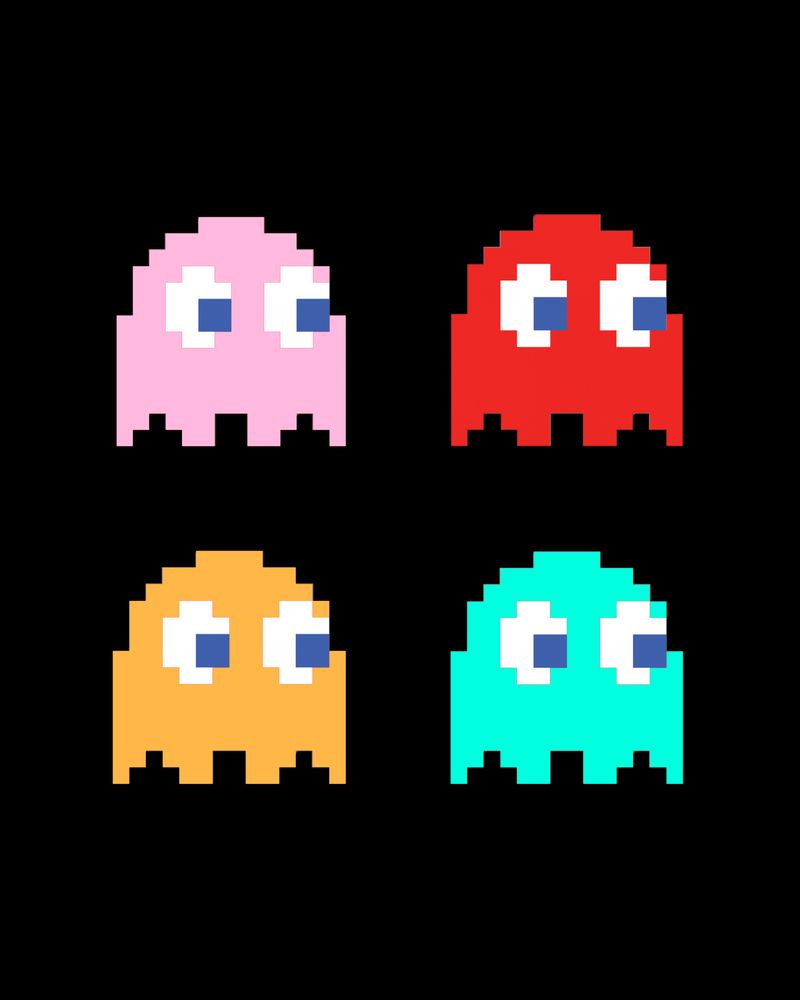

Iwatani’s choices are now pretty legendary: he chose “eat” as the first verb in gaming because it’s something every human has enjoyed. He chose ghosts as chasing opponents not only because they were simple to display on the screen, but because everyone knows ghosts. Iwatani specifically was thinking of the Japanese legend of the yokai spirits, but every culture has visitors from the unknown and all they need is eyes and sheets. Plus, the eyes are great and clear indicators — they show which direction each ghost is headed in.

His programmers are not to be forgotten either — Iwatani worked with a team of nine, and together, they built some impressively compelling personalities. Each of the ghosts has their own emotions (and programming): Blinky (red) goes aggressively straight for our player, Pinky (pink) and Inky (cyan) try to go around the player (sometimes moving in concert), and Clyde (orange) will patrol an area, though will occasionally run away from Pac-Man — he’s shy.

It worked, of course. Who doesn’t love Pac-Man? It’s elemental stuff in gaming, from the wakka wakka bleep and bloop sound design to the fruits that add up to a high score, and the power pills that allow the player to turn the tables, if only for a bit. The original arcade game’s ghosts move only in variations of scripted patterns (there wasn’t a random number generator available in the code). That surely only increased the addictiveness — it didn’t just feel like if you played enough, you could learn the patterns. You actually could (and players have).

Pac-Mania hits the US

In October 1981, the first Pac-Man machines arrived on US shores, brought here by Midway, a another amusement game maker that’s part of David Gottlieb’s Chicago scene, of all places. Pac-Man, and video games in general, are arguably the product of Count Goto Shinpei’s Japanese technology combined with good old Midwestern American salesmanship.

It was, as you may have heard, a hit. The winter was a bit slow (the official release was in December), but once the country thawed out for the summer, Pac-Man was everywhere. Across the whole year of 1982, Americans spent $416 million on coin-op arcade games, most of that on Pac-Man.

There are lots of stories of the arcade frenzies, and memories of putting a quarter on the machine, lining up to be the next to play in the hopes of beating the high score and leaving your name on the device. Namco certainly understood that Americans were likely to leave their mark — Pac-Man in Japan is Pakku-Man (which uses the Japanese sound for “chomp,” essentially), and when Namco created the American version, they wisely avoided the direct translation, “Puck-Man,” for fear that Americans would black out part of the first letter.

Odds are good that at least one Pac-Man machine was still vandalized — there were 400,000 of them sold, after all, and imagine the quarters that went through each one. Fortunes, reputations, and connections aplenty were made that summer in the arcades and gas stations and pizza parlors. Iwatani’s plan worked. Video games had arrived.

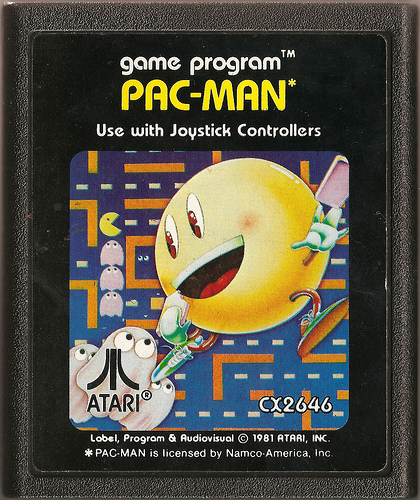

The highest peak on our Pac-Man tour stop here isn’t the original arcade release, however. Most of what people remember historically as the Pac-Man craze wasn’t all about the arcade version. Instead, it’s the Atari VCS 2600 release, about six months after the arcade launch, that really brought Pac-Man and video games to the forefront.

Think about it — the arcade game had steeped for an entire summer. People were loving it, playing it, and putting quarters into it. Atari (which had laid its groundwork well at that point — the 2600 had arrived in 1977, and solid releases like Breakout, Space Invaders, Asteroids, and Missile Command had built up a sizeable player base for the console in the years since) was ready to put some effort behind a real hit. Namco already distributed Atari’s games in Japan, so it made sense that Atari would distribute Pac-Man in the US.

As Pac-Man pulled people into arcades in 1981, Atari was also selling Ataris, and Atari knew Pac-Man was going to be a hit, so it threw as much of a marketing budget on it as possible (and started up the PR machine). The company manufactured a million copies even before launch, and even campaigned for April 3, 1982 to be “National Pac-Man Day.”

Pac-Man was so popular in the arcades that people were also lining up preorders before launch. But looking back, it seemed that actually making the game was one of the last things on Atari’s list — they hired a programmer named Tod Frye, just about six months before launch, to actually code and write the version of Pac-Man that would run on the console. This was long before game engines were common — every port needed to be recreated from scratch, hopefully as faithfully as possible, depending on the skill (or the care) of the programmer.

Frye is still a programmer, having worked at 3DO and other game companies since. And he has justified many of his choices — he was given a short schedule and a limited-memory cartridge to work with, and tried to follow Atari guidelines where possible, rather than focusing too much on the original game.

Nevertheless, the game he turned in, that Atari published as Pac-Man in 1982, is a complete disaster of a port. Most of what Pac-Man is remembered for isn’t there at all — there are only two ghosts, they flicker weirdly rather than showing color and personality, the pills are rectangular, and the sounds nothing short of grating, not to mention extremely off the mark. Even Atari knew there were issues — the company’s catalog says that the 2600 version “differs slightly from the original.” It has none of the charm or care of the arcade version, and anyone who bought the console game and played it without having been in the arcades in 1980 probably wondered what the big deal was after all.

Despite all of that, it was a huge hit anyway — the best-selling Atari 2600 game of all-time, it turns out, and at the time, the best-selling video game ever made. And here we are at the first summit of video games — the summer’s previous craze turned into a fad that had maybe gone on too long. Multiple cities drafted legislation against allowing minors to play video games unattended in public. A goofy fad single, “Pac-Man Fever,” peaked at number 9 on the Billboard charts in March of 1982. In the years since, Pac-Man has become a cultural icon — by 1988, there was a cartoon, and there have been a constant stream of releases since starring the little round gobbler, not to mention Nintendo’s own Super Smash Bros. series.

But we haven’t gotten quite there yet. Due in part to the combined success and terrible quality of the game, Atari made a licensed E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial game that.. well.. That’s a story we’ll discuss in a future column.

Until then, let’s think, as we finish this stop on our tour, about just how innovative Pac-Man was for its time. For the first time in almost ever, here was a video game not about the technology of missile systems or spaceships, or a mere simulation of war or sport. Here was a game about being human. It’s not just a feat of programming or marketing (though it is that for sure), but it’s about turning a vision into a success. It’s about creating something that you hope will resonate, and then seeing it resonate much farther than you expected. Count Gotō Shinpei understood that technology was about connecting his community. Iwatani knew how to connect things, how to make things work and turn on and play. And what he created ended up helping to connect the world.

Pac-Man is about something that we’ll see again and again on our tour here — it’s about putting personality into pixels, about creating a character, something to respond to and connect with, out of a set of rules, of wires and LEDs and code.

Thanks for coming along on the tour here. Next time: Shigeru Miyamoto’s big idea from the paper baths.